Hiram S Cody III, MD |

EDITED COMMENTS |

Quality control with sentinel lymph node biopsy Quality control with sentinel lymph node biopsy

Without question, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is equivalent to axillary dissection in its sensitivity for detecting nodal metastases and maintaining local control. More importantly, it results in less morbidity. However, SLNB is a procedure that has a learning curve. Early in one’s experience, it helps to take a course, to be mentored and to do a series of sentinel node procedures with a backup axillary dissection for validation before performing SLNB alone.

The best data we have suggest that the false-negative rate diminishes with experience, and surgeons should perform about 20 sentinel node procedures with a backup dissection to minimize their falsenegatives. When our group began to do sentinel node biopsy, our false-negative rate was about 15 percent. In evaluating those cases, we discovered that at least half of those patients had palpably suspicious nodes at the time of surgery. These were generally patients with a clinically negative axilla.

I believe a key element of the sentinel node procedure is to palpate the axilla after removing the blue and hot nodes. If any nodes are suspicious by palpation, they should also be submitted. By adding palpability to the definition of what constitutes a sentinel node, our own false-negative rate has dropped from 15 percent to four percent.

The learning curve for SLNB may not be as long as we originally thought because it was calculated at a time when the technique hadn’t been standardized. The ALMANAC trial has recently published its learning-curve results (Clarke 2004). In that trial, every surgeon was required to complete 40 sentinel node procedures validated by axillary dissection before beginning the trial.

From those 40 validated cases, they demonstrated that when a standard technique was employed from the beginning, most of the false negatives and failed procedures occurred in the first case. Beyond that, few false negatives or failures occurred, so maybe the emphasis should be on a standardized technique rather than the number of cases completed.

Technical aspects of SLNB

Variation exists in the SLNB technique. An emerging consensus indicates that it is best to use both blue dye and isotope. It appears that subdermal, intradermal and subareolar injections all work well and are probably better than peritumoral injections. Most of the breast and its overlying skin are draining into the same few sentinel nodes anyway.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy requires coordination between nuclear medicine, surgery and pathology. Before performing an SLNB, the nuclear medicine physician, surgeon and pathologist should agree on procedures. Regarding nuclear medicine, I think the one technical point that made the biggest difference for us was injecting the isotope intradermally. That modification has increased our success rate, bringing it close to 100 percent.

With regard to the actual surgery, it is important to perform the sentinel node procedure before completing the rest of the breast operation and to use good three-point retraction in the axilla and keep the tissue under tension. If you do that, it is a simple procedure.

It is also important to remove all blue and all focally hot lymph nodes. We take counts of the nodes ex vivo. At the end of the procedure, it is important to palpate the axilla to identify nodes that might be grossly involved by tumor, therefore not picking up the dye or the isotope.

We generally remove an average of two to three sentinel nodes per case. We will occasionally encounter a situation in which the axilla is diffusely hot and we could easily remove eight or 10 nodes; however, we have found that by removing three sentinel nodes we identify 98 percent of the positive lymph nodes. By removing four sentinel nodes, we identify 99 percent of the positive lymph nodes, so even when the axilla is diffusely hot, you don’t have to remove more than three or four sentinel nodes.

Morbidity associated with SLNB versus axillary dissection

At our institution, we conducted a study using a sophisticated instrument to assess postoperative sensation after both SLNB and axillary dissection. We found that SLNB resulted in approximately half the postoperative sensation morbidity that results from axillary dissection; however, we also found that SLNB had definite morbidity. It’s important for physicians to emphasize this in their discussions with patients.

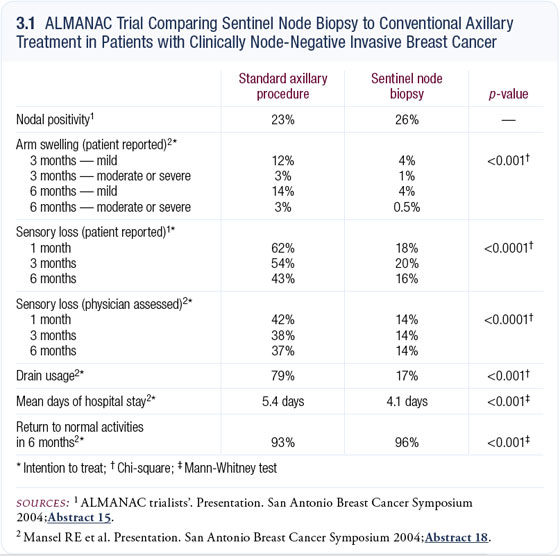

Patients may have pain, areas of numbness and injury to the intercostal brachial nerve. Lymphedema — which occurs in approximately 10 to 20 percent of axillary dissection cases — will also occur after SLNB, although much less frequently (approximately one to two percent of cases). Another important aspect to consider is the severity of the morbidity. It’s dramatic how much less symptomatology patients have after SLNB than after axillary dissection (3.1).

Pilot trial of intraoperative brachytherapy

At Memorial Sloan-Kettering, we are currently conducting a pilot study assessing the role of intraoperative brachytherapy. We are using the standard brachytherapy setup that we have used for years with rectal and gynecologic cancer and are delivering a single dose of radiation intraoperatively to the cavity of the breast excision. The study is limited to women over the age of 60 with tumors smaller than two centimeters. With an experience now of approximately 40 patients, we’ve found that this approach generally works well. It has an advantage in that it is a single intraoperative treatment and not 30 trips for postoperative radiation therapy. However, approximately 10 percent of patients had poor wound healing and required reoperation to excise the irradiated area and reclose the wound.

Select publications

|

Dr Cody is an Attending Surgeon of the Breast Service, Department of Surgery at Memorial Sloan- Kettering Cancer Center and a Professor of Clinical Surgery at Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York, New York. |

|